As of August, 2015

| Faculty/Department | Department of Communication Engineering and Informatics Graduate School of Informatics and Engineering |

|

| Members | Motoharu Matsuura, Associate professor | |

| Affiliations | IEEE (U.S.), Institute of Electronics, Information and Communication Engineers, Optical Society of America (U.S.) | |

| Website | http://www.mm.cei.uec.ac.jp/ | |

Fiber-optic communications, Optical signal processing, Optical networks, Wireless communications, Disaster resilience, Mobile phones, Lasers, Power transmission

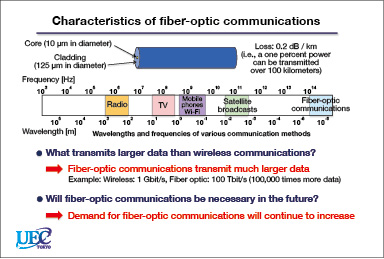

What is the fastest and largest-capacity surface communication method? Fiber-optic communications. As its name suggests, fiber-optic communications is a method of transmitting signals through an optical fiber, which is a long and narrow transparent fiber. Optical fibers consist of a small core and a cladding. Signals are transmitted by passing light through this core.

Recently, wireless communication usage has skyrocketed with mobile phones, smartphones, tablets, and other wireless devices. Wireless communications is a method of sending signals by propagating electromagnetic waves through air. While light is also a type of electromagnetic wave, because of light’s physical properties, optical signals have much higher carrier frequency than the electromagnetic waves used in wireless communications. In other words, the amount of data that fiber-optic communications can send is much larger than that of wireless communications (see Figure 1). This is why fiber-optic communications are nearly always chosen for applications where large volumes of data must be conveyed, such as trunk lines and backbones at the core of a communication system.

But just how much data can a fiber-optic communication line transmit? At the experimental level, optical-fiber data transmission speeds of one petabit (Pbit) per second have been obtained. One petabit is one quadrillion (1015) bits. And how much data is that? “It’s equivalent to sending 5,000 two-hour HDTV movies in one second” (Associate Professor Matsuura). Putting it another way, if 5,000 users try to download a two-hour HDTV movie at the same time, all the downloads will be completed in just one second. Suffice to say, it’s an incredible amount of data.

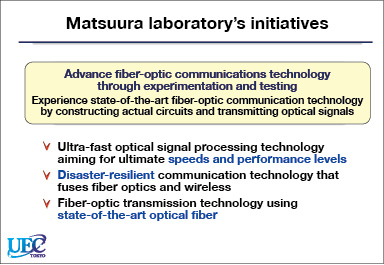

The Matsuura laboratory’s research looks at ways of advancing fiber-optic communications. This research covers three basic topics. The first research topic is ultra-fast optical signal processing technology with an aim toward attaining the maximum possible speeds and performance levels. The second topic is disaster-resilient communication technology that fuses fiber-optic communications and wireless communications, called “radio-over-fiber”. And the third is research into fiber-optic transmission technology using state-of-the-art optical fiber (see Figure 2).

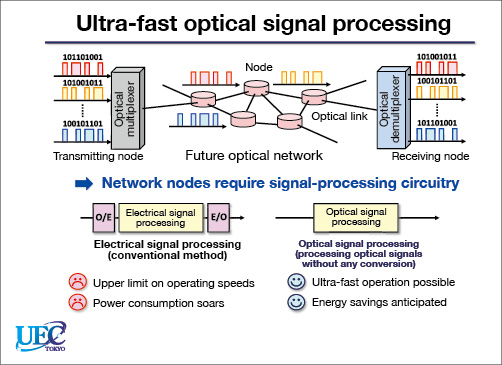

The first topic, ultra-fast optical signal processing technology, is a key technology for future optical networks. Optical networks consist of optical nodes where optical signals are sent and received and optical links that join the nodes (see Figure 3). At present, optical nodes convert input optical signals into electrical signals to process the signals with electronic circuitry. The processed electrical signals are converted back to optical signals and output on the optical links. With this method, however, increasing the speed of the electronic circuitry results in steep increases in power consumption. Since higher power consumption is no longer feasible given today’s focus on energy conservation, higher speeds than what we have today may well be impractical.

As an alternative, researchers are looking at equipping nodes with optical signal-processing circuitry, which performs signal processing on unconverted optical signals. Research is going in this direction because optical signal-processing circuitry operates at much faster speeds than electronic circuitry while, it is hoped, consuming much less power.

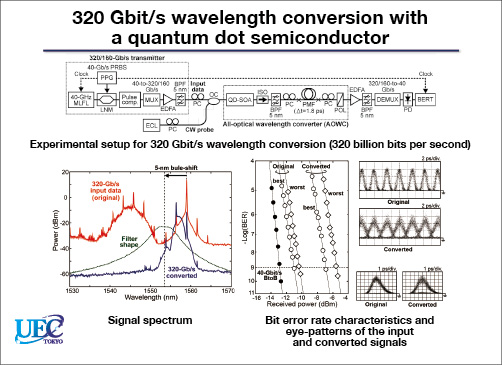

One example of the Matsuura laboratory’s research into optical signal processing is ultra-fast wavelength conversion, developed in partnership with the Eindhoven University of Technology in the Netherlands. The laboratory has demonstrated wavelength conversions of optical signal at speeds of up to 320 Gbit/s (see Figure 4).

Past research into fiber-optic communications has, by and large, put its energy into setting new communication speed records. Certainly, research attempting to reach higher speeds will remain important, as the total amount of data humanity deals with is expected to escalate over time. Nevertheless, from Associate Professor Matsuura’s viewpoint, research looking at other aspects than just communication speeds will become critical as well in the coming years. One of these directions, as mentioned above, is disaster-resilient communication technology.

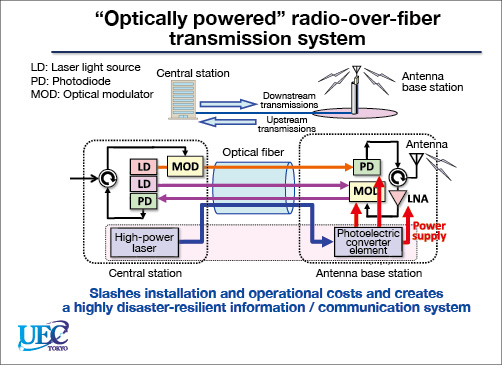

In today’s mobile phone systems, wireless communications are used between antenna base stations and devices (smartphones, mobile phones, etc.) while fiber-optic communications are used to send data between antenna base stations and central stations. This is called “radio-over-fiber” transmission system. Central stations have backup power supplies in case of power outages due to natural disasters or other events. Antenna base stations, on the other hand, are not equipped to deal with power outages because of cost constraints. Therefore, if some natural disaster or event cuts the power supply to an antenna base station, the mobile phone system in the area around the antenna base station will go down.

The Matsuura laboratory is working on this problem by researching how to supply power to antenna base stations using optical fiber (see Figure 5). The technology being researched delivers power from a central station to antenna base stations via optical fiber using high-power laser light. This means the same optical fiber transmits both signals and power. Interference does not occur since the laser light used for signal propagation and the laser light used for power transmission are at different wavelengths. One advantage of this methodology is the completely independent control over signal transmission and power transmission.

There are still many technical hurdles to be overcome before it is feasible to supply power to antenna base stations over optical fiber. This is why the Matsuura laboratory has a strong desire to engage with corporate partners on joint research projects in this area.

At the Matsuura laboratory, emphasis is put on experiencing state-of-the-art fiber-optic communication technology first hand by constructing and experimenting on actual optical signal circuits. Of particular importance are hunting down, selecting, and combining existing component technologies from many different fields. Researchers discover new utility value by fusing various elements that at first seem totally unrelated. This is why Associate Professor Matsuura preaches about the need to study many technologies from diverse disciplines.

In research, there is no such thing as a single correct answer, which is different from exams or projects in high school. What is important is to first generate as many ideas as possible through the process of proposing research topics and paring away at research problems. After first formulating dozens of ideas, examining them, and throwing nearly all of them away, new research topics and solution methodologies begin to come into focus. Associate Professor Matsuura’s hope is to nurture students who can keep coming up with new ideas without worrying about mistakes.

[Interview and article by Akira Fukuda (PR Center)]