As of August, 2015

| Faculty/Department | Department of Informatics Graduate School of Informatics and Engineering |

|

| Members | Naoaki Itakura, Professor | |

| Affiliations | Society of Instrument and Control Engineers; Institute of Electronics, Information and Communication Engineers; Japanese Society for Medical and Biological Engineering; Japan Society for Physiological Anthropology | |

| Website | http://www.se.uec.ac.jp/~ita/ | |

Eye-gaze input interface, brain computer interface, eye gesture, eye glance, visual evoked potential (VEP), electromyogram (EMG), road traffic simulator, human interface, modeling

As part of our research to elucidate the mechanisms of bodily functions and human behavior by strategically employing bioengineering and ergonomic approaches, our laboratory is engaged in a study of muscle contraction mechanisms and muscle fiber composition based on electromyograms (EMG) waveform analysis; studies of input interfaces based on eye movement and electroencephalogram (EEG) of humans; and studies involving road traffic simulators.

We have developed an algorithm that extracts only the propagating waves from an EMG. The algorithm has been used to demonstrate that changes in the levels of fatigue or the contractile force of muscles are reflected as changes in the velocity and amplitude of propagating waves in EMG. Our study has shown for the first time the complex mechanisms of muscle contractions, which involve a variety of muscle fiber types.

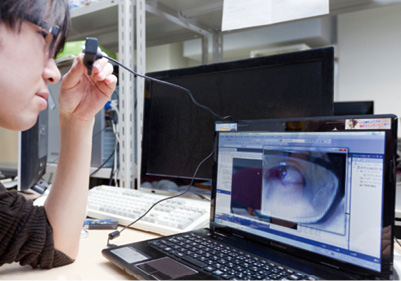

Numerous studies already exist on eye-gaze input, a form of an input interface that uses eye movements (line of vision), wherein the user selects a character by gazing at it. However, in almost all eye-gaze input interfaces, any movement of the head from its original position results in incorrect identification of the selected character. The head must remain in a fixed position.

To overcome this problem, our laboratory has developed an eye-gesture input interface, in which the character selected for input is determined based on a combination of directions in eye movement. Since this system does not require the absolute point of the gaze to be determined, there is no need for the user’s head to remain fixed.

The interface has been improved further to develop eye-glance input, wherein momentary eye movement is used to determine the character selected. With eye-glance input, combinations of eye movements that occur while glancing at an object have been extracted from the various movements of the eye used in eye-gesture input. With the actual eye-glance input interface developed, users can enter 20 characters using glancing movements in four directions on a specially-designed screen.

When humans are subjected to a blinking stimulus, VEP specific to that stimulus are generated. One interface called the brain computer interface uses VEP to identify the target being viewed by a person based on the specific VEP and blinking stimulus. Our laboratory is unique in having proposed several interfaces that combine two different sets of VEP: steady-state VEP (SSVEP) based on blinking stimulus and featuring a frequency of 3 Hz or higher and transient VEP (TRVEP) based on frequencies of 3 Hz or lower.

Research and development on a road traffic simulator are proceeding at our university as part of a joint study with the N. Honda laboratory. The various maneuvers (logic) required while driving, such as following a car in front, making right/left turns, or passing a car have been categorized into numerous types and modeled to develop a simulator that incorporates the drive logic (MITRAM). The MITRAM has been adopted by Kyosan Electric Manufacturing Co., Ltd. as a system for traffic signal evaluation and is currently in use. Our laboratory regards the modeling of human behavior as an integral part of research on understanding humans and has spent many years on modeling various drive maneuvers and incorporating the results into computer simulations.

We believe in the importance of departing from conventional ways of thinking and of trying out new ideas and new approaches. This is how new discoveries are made. For example, conventional EMG studies use only simple integral analysis and/or frequency analysis, imposing limits on the information that can be retrieved and making it impossible to fully understand the mechanisms involved in muscle contractions. In contrast, we developed a propagating wave detection method, an algorithm based on the waveform interpolation technique used in the sampling theorem. This approach uses the homothetic ratio, amplitude ratio, and wavelength ratio parameter to detect propagating waves in EMGs. Our algorithm lets us infer muscle contraction mechanisms in detail.

The TRVEP used in brain computer interfaces required repeated measurements and calculations of the time synchronous averaging of waveforms approximately 300 milliseconds after stimulation to obtain a clearly defined VEP component. It was naturally assumed that a blinking stimulus was required to achieve frequencies 3 Hz or below (interval of 300 milliseconds or greater). Since a large number of waves (about 30) had to be measured to calculate the time synchronous averaging, a single measurement run lasted nearly 10 seconds. Our laboratory chose to discard this assumption and to perform experiments using blinking stimulus of much shorter intervals. We found that it was possible to use blinking stimulus of frequencies of up to 15 Hz without adversely affecting the results. Stimuli of higher frequencies reduce the time required for measurement to about two seconds.

Professor Itakura believes that real-world applications are an important factor in biological information utilization. For example, the eye-glance non-contact input interface eliminates the need for a touch screen and requires only a small, low-cost and safe device. The design, which allows users to input a whole array of characters simply by changing the direction of the glance in one of four directions, is easily modified to create an input interface for conventional touch screen systems. We expect it to achieve success as an input interface for small touch screens, like those found in smartphones.

We are also exploring ways to apply our EMG wave propagation analysis system to actual products. Since this system lets users make objective assessments on the effects of training on muscles, we believe it might gain popularity as a simple-to-use device for evaluating the effectiveness of training programs for athletes and the exercise programs offered at fitness centers.